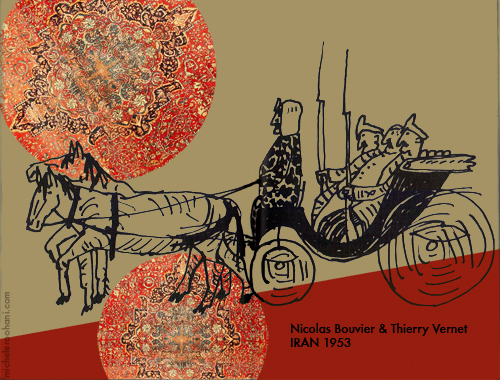

This is my blog’s fourth Anniversary issue and what better subject than the amazing Nicolas Bouvier! He traveled from Geneva to the Khyber Pass in Afghanistan in 1953-1954 with his painter friend, Thierry Vernet.

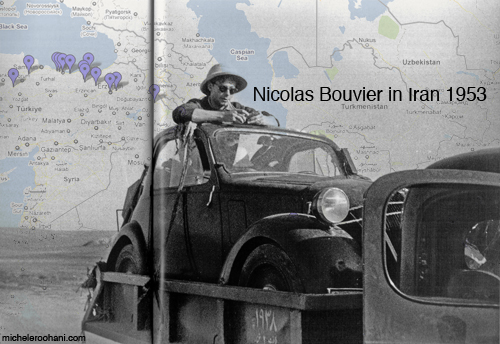

I read his great book, The way of the world, last year; it started a bit slow but once that he got to Iran, I was hooked. This map traces their journey from Europe to Asia where Bouvier starts in Geneva and ends in Afghanistan:

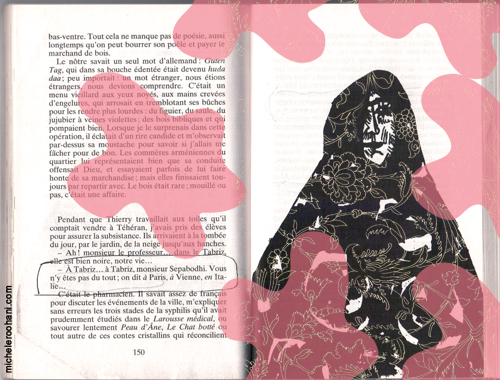

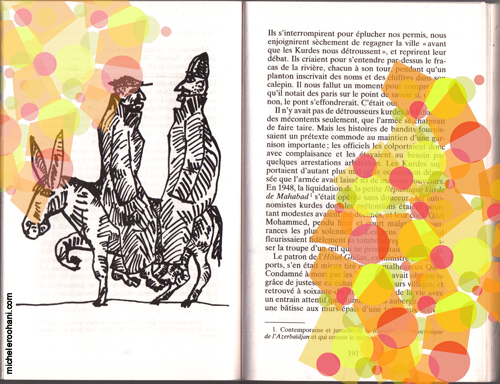

His friend, Vernet, has kept a visual jounal by drawing what they see together and what Bouvier writes:

These images are my interpretation of their work and an homage to this delightful journal. “Ten years in the writing, The Way of the World is a masterpiece which elevates the mundane to the memorable and captures the thrill of two passionate and curious young men discovering both the world and themselves.”

They traveled with a small Fiat Topolino (above and below) that took them through hell and paradise!

What was striking about this little book was the fact that I didn’t have to lower my expectation of excellence: Bouvier writes with the ease of the poet that he is and the attention of an enthusiastic humanist…

He talks about “women buried in their floret tchador”: femmes ensevelies dans leur tchador à fleurettes.

He talks about how “Iran, the old aristocrat, who has experienced everything in life … and forgotten a lot, is allergic to ordinary remedies and needs special treatment. The gifts are not always easy to give when children are five thousand years older than Santa Claus.”

After finishing the book, I got curious about the writer and started the “research”! I compiled many images about this master Iconographer, I watched many of his interviews—from his youth until the last years of his life— and he sounds as fresh at the end as he did in the beginning.

The Swiss television has a great archive on the subject.

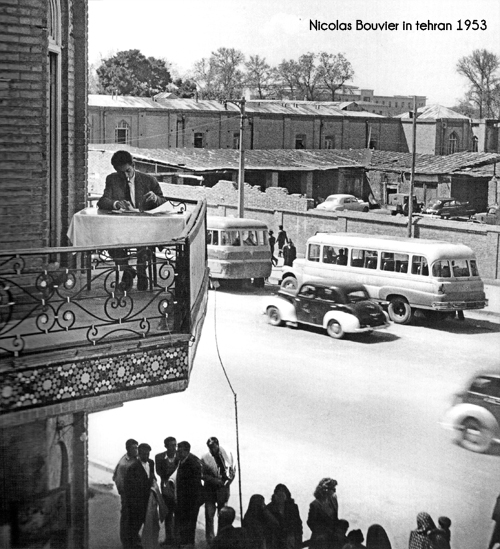

I have to admit that the year they spent in Iran was the most interesting to me— even though Serbia, Turkey, Pakistan and Afghanistan had their own exhilarating charm. He even talks about my old school, Jeanne D’Arc of Tehran, in the years before my birth. The next couple of pictures of Bouvier are from their time in Tehran; this one from a modest hotel’s balcony:

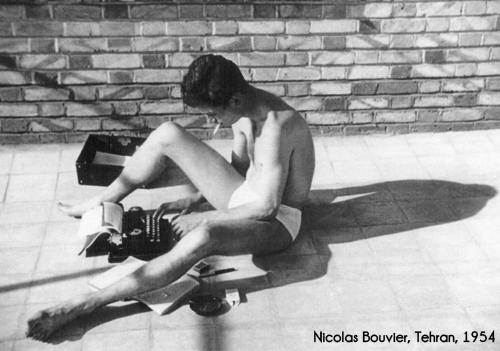

He’s typing in the nude in the heat of the Iranian summer:

Most of all I loved the winter they spend in North west of Iran, in Tabriz:

The way he describes the long quiet winter in that city transports the reader to the depth of our common humanity; I laughed when he talks about the smell of hot Persian breads, Sangak and Lavaash in the snow or when he describes the frozen mustaches and beards of men in the freezing cold, the boiling water of samovars and the fact that everybody thinks only about three words: tea, coal and vodka!

Speaking of Persian breads, Bouvier suggests that only a very old country can make luxuries out of most banal routines; this bread has been thirty generations and a few dynasties in the making…

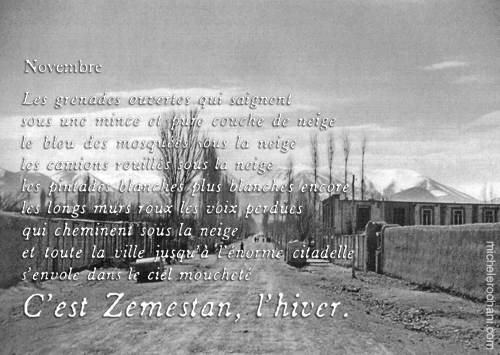

I was overwhelmed with nostalgia reading his beautiful poem about the onset of winter (Zemestan in Persian) in Tabriz:

I couldn’t find it in English so I translated it myself; first the original in French:

Novembre

Les grenades ouvertes qui saignent

sous une mince et pure couche de neige

le bleu des mosquées sous la neige

les camions rouillés sous la neige

les pintades blanches plus blanches encore

les longs murs roux les voix perdues

qui cheminent sous la neige

et toute la ville jusqu’à l’énorme citadelle

s’envole dans le ciel moucheté

C’est Zemestan, l’hiver

Tabriz, 1953

November

Bleeding open pomegranates

under a thin layer of pure snow

the blue of the mosques in the snow

rusty trucks in the snow

white guinea fowl whiter still

long red walls lost voices

who walk in the snow

and the whole town to the huge citadel

flies in the mottled sky

It’s Zemestan, winter

Tabriz, 1953

These images are based on the following books:

Bleu Immortel and The way of the world.

I read the “The way of the world” in french (L’Usage du Monde) but it has been lovingly translated by Robyn Marsack; I recommend it to all of you.

Que votre ombre grandisse or May your shadow grow!